Epigraphic evidence for the year of the Mahābhārata war

Inscriptions play a vital role in the re-construction of the past, as they are contemporaneous to the time they were made. In the Indian context “the inscription clears the myth related to ancient history of India as it is regarded authentic than other sources” according J. J. Fleet. Kali Yuga starting at 3101 BCE is the one and only date repeatedly authenticated by many inscriptions, majority of them from South India. The continuity of indigenous dynasties and the relative calm experienced in South India had enabled the preservation of thousands of inscriptions, of which 60,000 are found in Tamilnadu alone, according to Dr. R. Nagaswamy, the leading historian and epigraphist.

According to him, “From administration to education and judiciary, everything in this land is documented,” until the country was taken over by the East India Company. Until 1750 CE, there was continuous documentation of financial activities including donations made by individuals, inscribed on stones or metals or palm leafs. Of these palm leafs were re-written every 300 to 400 years, due to wear and tear. Even women were engaged in replicating palm leaf manuscripts in times of need. Writing style might have changed with time but the original content was not changed.

Stones or metals were preferred for recording the transactions involving money, land and gift. At times the inscribed metal plates had undergone wear and tear with the vagaries of time. In some cases they might have been lost. Sometimes the possession of the land granted by a king might have undergone changes after many generations, requiring the re-drawing of the boundaries by the king of that time. In all these occasions the dāna-patra-s were replaced without fail since most of these inscriptions were land deeds or about donated lands (dāna patra) with or without tax exemptions on the produce. They were rewritten under the authority of the king of the day by the royal officer and the witnesses as per the procedures laid down by the Dharma Sāstras.

Writing on this Dr. R. Nagaswamy points out that the purpose of re-writing the dāna-patra is also inscribed in the same plate as “Lekhya suddhi” for correcting defects in writing or “nasa dosha nirakartum” for replacement of a lost dāna-patra. In the case of continuous possession beyond human memory, mere possession is recognized as a mode of proof by Dharma Sāstras. The re-defining of the boundaries is done in a new dāna- patra by retaining the original details of the gift. The writing style and the boundary names are likely to be of recent origin in such cases. This probability is quite high in the dāna-patra written 5000 years ago, say, in the inscriptions ascribed to Janamejaya, the great grandson of Arjuna — if possession or enjoyment of the donated land (bhukti) had continued with the descendants of the original recipients.

It is not easy to reject a dāna-patra or any inscription as fabricated. It is not difficult either to find out if it is a forged one. Any defects in writing with reference to the recipient’s name or the measurement or the extent of the donated land would have been rectified immediately on receiving the dāna-patra. The date elements are also reliable except in rare cases where human errors might have crept in due to the gap between the preparation of the dāna-patra and the actual date when the king or the donor had made the gift. They can be rectified if sufficient clues on the date are available in the inscription. So we need to take note of these issues in the inscriptions before proceeding to quote them as primary evidence for the date of the Mahābhārata war.

Choice of inscriptions for dating.

Not all the inscriptions carry all the elements needed to derive a date. Kali Yuga being pivotal to dating the inscriptions, those with Kali Year or Śaka year are helpful in dating. For example the date of King Uttama Cola is conclusively derived from his inscription giving the Kali year 4083 when he was running his 13th regnal year. It was 982 BCE (3101 BCE — 4083). The mention of the regnal year of the king is a useful factor in cross-checking with the end of the tenure of the previous ruler.

The second most desirable feature in an inscription is the Year name. The sixty year cycle, each year with a distinct name, is used for the years of Kali Yuga and continues to be in vogue even today. Pramathi was the first year of Kali Yuga, established by inscriptions and also by Aryabhatiya. Aryabhata refers to the lapse of 3600 years (60 x 60) since the beginning of Kali Yuga when he was 23 years of age. At that age the vernal equinox coincided with the sidereal equinox (zero ayanamsa) according to the commentators, based on the planetary positions derived from his work. That year was Pramathi! So the first year of the sixty times of sixty years had Pramathi running. In other words, Kali Yuga started in the year Pramathi.

The Year name offers an excellent cross- checking to authenticate the year given in an inscription if that carries the Kali or Śaka year too. As a sample case let me take up the derivation done by Mr. Vedveer Arya overlooking the year name given in an inscription. This inscription found in Shivamogga district of Karnataka refers to an annular solar eclipse (valaya grahana) in the Śaka year 861. Fortunately the inscription also furnishes the year name as “Vilambi”.

The writer focused only on the year number and derived the date as 277 -278 CE from an unknown and an un-established Śaka of 583 BCE, (not belonging to the Kali Yuga) and picked out 20th February, 277 CE. This year corresponds to the year Durmukha, and not Vilambi. The following year starting from Caitra was Hevilambi and not Vilambi, thereby rejecting a probability that it could have referred to the next year starting from the next day. Both the derived year and the assumed Śaka are found wrong.

Checking the Śaka year 861 in the inscription with Śālivāhana Śaka of Kali Yuga, the year is 939 CE (78 CE + 861).Vilambi was running in 938–939 CE! The Śaka year and the year name had matched. This gives solid proof for the year of the inscription as 938–939 CE. The Year name and the number of Śaka years are thus very vital for dating.

Once the year is known, the exact date is offered by the group of Pancāṅga elements such as the month, tithi, paksha, star and the week day. Absence of one among the last two (the star and the week day) may not affect the dating effort, because all the other elements with or without one of the last two, match only on a particular day in a Śaka era of Kali Yuga. Any scribal error in such a combination can be sorted out.

In the overall analysis, the inscription should include the following for dating purpose:

• Year number of the Śaka or Kali Yuga

• Year name

• Month, pakśa, tithi, star or / and weekday

Clarification on Śaka eras.

Often doubts are being raised on the identity of the Śaka era in the inscriptions. Certain kings had initiated their own eras, but all of them followed the time elements of Kali Yuga only (Pancāṅga elements). For establishing the year of Mahābhārata, only the Kali Maha Yuga and its sub eras are valid, for the reason that Kali Yuga started at the time of departure of Krishna from this world.

There are only six Śaka eras in Kali Maha Yuga, of which we are in the third Śaka of Śālivāhana. The first was Yudhishthira Śaka that lasted for 3044 years (57 BCE) followed by Vikrama Śaka. This lasted for 135 years and was replaced by Śālivāhana Śaka in 78 CE. The classification of these eras with their respective duration is found written in an astrological text called “Jyothirvidabharana” authored by Kālidāsa, a court poet of the King Vikramāditya of Paramāra dynasty, who founded the 2nd Śaka of Kali Yuga in the year 57 BCE. The authenticity of this text is attested from the fact that the author had stated in the text itself that he started writing it in Visakha 3068 of Kali Era (33 BCE) and completed in Kartika month of the same year.

The classification of Kali Yuga into six Śaka eras as given in this text is reproduced in the table below.

The complete plan of Kali Yuga of 4,32,000 years already in existence implies that it was devised at the time Kali Yuga computation was handed down. This was done by ‘Purā-vidah’- the learned people of the past who declared that Kali Yuga started on the day Krishna left for his higher realm, as per Srimad Bhagavatam.

In epigraphy, many a time there is just a reference to the number of Śaka years, without giving the name of the Śaka era as in the Shivamogga inscription quoted earlier. However the mention of Kali Yuga or Kali years could only refer to one of the Śaka eras of Kali Yuga and not an independent era of a king or dynasty. For instance, the Aihole inscription of Pulikesin II makes a specific mention of the years in ‘Kalau-kāle’ (in Kali’s time). This goes without saying that the Śaka mentioned therein belongs to Kali Yuga. By subtracting the Śaka years from the Kali years, it is known that the inscription had referred to the Śālivāhana Śaka. This is an important inscription vouchsafing the abdication of the throne by the Pandavas following Krishna’s exit at the beginning of Kali Yuga.

For dating Mahābhārata, only Janamejaya’s inscriptions are the primary evidences. The factors derived above offer a template for analyzing his inscriptions to arrive at the date of Kali Yuga and the year of Mahābhārata from that.

Inscriptions assigned to the king Janamejaya

Parikshit, the son of Abhimanyu who ascended the throne on year one of Kali Yuga following the departure of Krishna and the Pandavas, ruled for 60 years, according to Krishna’s version in Mahābhārata His son Janamejaya had therefore taken up the reigns in Kali year 61. Sometime later he conducted the Sarpa yāga that was attended by Vyasa who caused the recital of Mahābhārata at his request. At the time of Sarpa yāga Janamejaya had made donations to Brahmins, some of whom had come all the way from the region of Karnataka to take part in the Sarpa-yāga. The commitment was made then but actually executed when the king was journeying down the southern regions of India as part of Dik-vijaya. This expedition seems to be in connection with the Asvamedha yajna he conducted sometime after the Sarpa yāga.

So far four copper plates have been discovered in Karnataka, all of them referring to the gift of land by Janamejaya, the son of Parikshit. Of these three appear with the same praśasti, but the year number and the year name are missing. They refer to land donations offered at the Sarpa yāga to the Brahmins of Begur, Kuppedgadde and Gauj of Shivamogga district.

The other inscription is found in the possession of Bhimanakatte maṭha, in Tirthahalli taluk of the same district. This was given by Janamejaya while seated on the throne of Kishkindha to a maṭha situated at a place where the Pandavas stayed during their exile. The king had donated the land by pouring the water of the river Thungabhadra on the recipient’s hands. This inscription having all the factors needed for dating makes it a first rate primary source to arrive at the date.

Deducing the year of the Mahābhārata war from Janamejaya’s inscription.

This copper plate inscription found in the custody of Bhimanakatte maṭha was first reported in page 378–379 of December 1872 issue of The Indian Antiquary by V. N. Narasimmiyengar. It was also reproduced in page 349 of the eighth volume of Epigraphia Carnatica by Lewis Rice published in the year 1904. Pandit Kota Venkachelam used this inscription as an evidence for the Mahābhārata war in his book “Age of the Mahabharata war.”

The maṭha possessing these copper plates belonged to the Madhvācārya sect that came into existence only in the 13th century. There was no information on how the maṭha came to possess these plates. But the name of the place, Bhimanakatte has a striking connection with Bhīma of Mahābhārata who was said to have re-incarnated as Madhvācārya. A maṭha had existed when Janamejaya visited this palce. A maṭha continuing to exist in the same place having in its custody the copper plates guaranteeing possession of the land can have only one plausible reason that it started following Madhvā tradition later. This copper plate is now preserved in the archaeological museum of Shivamogga.

Katte in Kannada means bank or shore. This katte seen with huge blocks of stone is supposed to have been built by Bhīma when the Pandavas were staying here during exile. Writing about this katte in The Indian Antiquary, Rob.Cole, the Superintendent of Inām Settlements, Mysore, refers to this katte as a dam and says, “Whatever may be the origin of the maṭha, the dam bears undoubted traces of the wondrous magnitude of the works of those days.” This region undisturbed by any invasions seems to have continued to maintain the status quo for thousands of years.

Bhimanakatte (Source: http://bheemanakattemutt.com/photos/)

The river in the northern boundary of the donated land was known as Bhīma River in the records of Lewis Rice. This appears as Khūma River in the previous record of the Indian Antiquary. However the writer of the Antiquary article acknowledges the presence of many errors in copying and there is scope to say that Khūma was rectified to Bhīma by Lewis Rice.

Munivrinda maṭha was the original name found in the inscription. The inscription says that it was situated in Vrikodara kshetra — Vrikodara being another name of Bhīma. Within a century of Bhīma’s association with this place, it got named after him. This place was in the west of Sītāpura. The grant was given for the worship at the temple of Sītāpura to Kaivalyanātha, the disciple of Garudavāhanatirtha Sripāda of Munivrinda maṭha. King Janamejaya, seated on the throne of Kishkindha had given the gift in front of the sannidhi of Harihara to the ascetic, by pouring the water of Thungbhadra in his hands on the day of the solar eclipse, for the sake of his parents to obtain Vishnu loka. This inscription as given in the pages of Epigraphia Carnatica is reproduced below.

Written in Devanāgarī characters, the date was the 89th year of Yudhiṣṭhira Śaka, in the year Plavanga, in Sahasya month (Pushya month), on Saumya vāsara (Wednesday). It was uparāga- samaya — at the time of an eclipse. This information is sufficient to deduce the date in the astrology software (Jhora).

The 89th year of the Yudhishthira Śaka in the year Plavanga exactly matches with the Kali Yuga beginning at Pramathi. Parikshit ascended the throne on Kali 1, in the year Pramathi. Sixty years after him, Janamejaya came to the throne on the 61st year of Kali Yuga when the next round of sixty years started in Pramathi. On his 29th regnal year, Plavanga was running which happened to the 89th year of Kali Yuga or Yudhishthira Śaka. The year number matching with the year name is proof of authenticity of the inscription.

Having zeroed in on the year, the Pancāṅga elements are to be checked now. A solar eclipse did occur in Pushya month of that year when checked with the settings of Surya Siddhanta ayanamsa. (All these — the year name, the month and the solar eclipse do not go together for any other settings of ayanamsa). However, the weekday turns out to be Friday (Śukra vāra), not Saumya vāra. With other details falling in place, the change from Śukra to Saumya seems to be memory-error due to the gap between the actual of time of donation and the time of preparing the copper plates. The year number, the year name, the month and the eclipse are easily retained in memory while the day could have been erroneously written. The recurrence of this combination being impossible, the weekday is rectified to Friday.

The simulated version for this date shows the sun at a distance of 18 degrees from Rahu, the nearest node. At this distance the eclipse was partial. King Janamejaya had made the donation in the afternoon of the day when the sun was partially eclipsed.

With the 89th year falling at Plavanga, this inscription offers the best corroboration for Kali Yuga starting at Pramathi. It started with the ascension of Parikshit to the throne when the Pandavas decided to renounce everything. This was caused by the irreparable of loss of Krishna’s presence in this world. So the year of Pramathi, coming 88 years before Janamejaya made this grant, is irrefutably established by this grant as the year of abdication of the throne by the Pandavas and the departure of Krishna from this world. That was the first year of Yudhiṣṭhira Śaka, the first Śaka of Kali Yuga by which is established that that it was the first year of Kali Yuga.

Thirty five years before that, the Mahābhārata war had occurred. Thirty-five years before Pramathi, the year of Krodhi was running! That was the year name of the Mahabharata war. This year in modern calendar date is 3136 BCE ((3101 BCE + 35). This is how the dates of the past events are established. This date must be validated by the chronology of events given in Mahābhārata, the Pancāṅga features of those events and the planetary combinations associated with those events.

The objections and the replies.

1. Initially there was resistance to accept the antiquity of this inscription that establishes Mahābhārata as a true history. Lewis Rice doubted that the year 89 could have been 1289 of Śālivāhana Śaka when Plavanga was running. The year 1367–68 (converted into modern calendar year) was indeed Plavanga but there was no eclipse on Pushya Amāvāsyā of that year and the week-day also did not match. (January 18, 1368).

2. Rice also doubted the use of the term ‘Jayābhyudaya’ which he pointed out as being present in other inscriptions for the dates of Śālivāhana Śaka. In the same breadth he conceded that this expression is found only in the same region of Shivamogga and not anywhere else.

Abhyudaya means increasing or beginning. Increase of Jaya or victory was invoked by Vyasa at the beginning every parvan of Mahābhārata. The same verse on Jaya also appearing at the beginning of the chapters of the Puranas, it is undersrtood that Jaya is a generic term used as invocation at the beginning of any work during the time of Mahābhārata. It had continued in the inscription of Janamejaya of that time. The same style found only in the region of Shivamogga goes to show the retention of this tradition in this region since the time of Janamejaya.

3. The signature “Sri Varāha” is in modern Kannada letters, according to Lewis Rice. The opening words, “Sri Ganādhipataye Namaha” is also suspect in his eyes that he prefers to date this grant to Bukka Raya or his son Harihara’s time in the 14th century.

Only the opening invocation and the signature looking recent in origin, the presently available plates were likely to have been re-written sometime in the last 2000 years. The veracity of the grant can be checked with the boundaries mentioned therein.

The boundaries of the grant of Janamejaya.

This grant specifically states the donated region as where the great grandfather of the king had stayed–‘asmat prapitāmaha Yudhishthiradhisṭhita’. The boundaries of Munivrinda kshetra given in this grant are recognizable by the rivers on the three sides. On only one side, the presence of Agastyāṣrama is mentioned. It is on the south. Today no such Aṣrama can be located to the south of Bhimanakatte.

Of the three rivers on the three sides, the river Thungabhadra continues to be flowing to the east of the maṭha. There is no river seen in the north of Bhimanakatte, but a tributary of the river Thunga is seen running towards the north for some distance today. In the earlier times it could have turned towards west forming the northern boundary of the grant given to the maṭha of Bhimanakatte.

The grant refers to Pāṣāṇa River on the west of the donated land. Pāṣāṇa is a Sanskrit word meaning stone. Today Varahi River (Halady River) runs in this region, originating from the Western Ghats. Twenty five kilometers from its origin it passes through Kunchikal falls, (Kunchikal means ‘small stone’ in Kannada) that causes the river to jump and fall on stones as it cascades down, perhaps earning the name Pāṣāṇa (stone) in olden days. The transformation of the name from Sanskrit to Kannada (Kunchikal) or to another name Varahi, does indicate a long passage of time since the river was called Pāṣāṇa. Today the flow of this river is halted for a hydro-electric project causing a reservoir on the west of Bhimanakatte.

The presence of two big rivers on the two sides and traces of another in the north do confirm the authenticity of the donation. This grant seemed to have come under the scrutiny of the British authorities for verification of the legal ownership which is made out from Rob.Cole’s article in the same issue of the Indian Antiquary. He had verified and found the record straight.

He tried to trace the origin of the Matha to Mādhvā sect, but gave it up on coming to know that it was more recent in origin compared to the date given in the copper plates. The deep antiquity of this grant was acknowledged by him by referring to the awesome structure of katte supposed to have been built by Bhīma.

This being a dāna-patra, there is no need for anyone at any time to invoke Janamejaya’s name and the name of Yudhishthira, for, it is not going to make any difference to the legal possession of the land. So no controversy is there about this grant. It stands as strong evidence against any controversy on the date of Mahābhārata as anything other than 3136 BCE.

Similar grant in Kedarnath.

A similarly worded land grant given to the Usha maṭha of Kedarnath on the same day of the solar eclipse by the King Janamejaya is reported by Kota Venkatachelam in his book. The only difference appears in the location of the king. He was at Indraprastha in the Kedarnath grant, while Kishkindha is mentioned in the Bhimanakatte plates. A notable omission is the link to the presence of the Pandavas in the past. Bhimanakatte grant covered the places visited by the Pandavas during their exile, but no such reference is found in the Kedarnath plates — though Bhima’s name is connected with the formation of the Kedarnath temple in the temple’s history.

Usha Matha was associated with Usha, the wife of Krishna’s grandson. It is logical to expect of a king on coming to know of the historicity of his ancestors, to perpetuate their memory in places associated with them. It is also likely he personally visited those places though he committed to make the donation on the most appropriate day of solar eclipse. The grant could have been made at Indraprastha, but given personally at the time of the king’s visit to Kedarnath. Both the grants were given for the sake of the parents of Janamejaya — for attaining Vishnu loka in Bhimanakatte, and Shiva loka in Kedanath grant.

Both the grants have identical verses in naming the witnesses (natural forces such as the sun, the moon, the fire, the sky and so on), the manner of protection and the retribution if anyone usurps the donated lands. Two additional verses are found in Bhimanakatte grants. There is no signature by any official in Kedaranth grant though Lewis Rice mentions ‘Sri Varaha’ in Bhimanakatte grant.

Two similarly worded grants issued on the same day by the king Janamejaya to two places separated geographically very far, but connected with Mahābhārata characters, make them genuine and acceptable as first rate evidences.

Ramayana locations

Janamejaya was known to have made Dik-Vijaya to the South from the three other inscriptions found in Shivamogga. It is likely that he had a royal seat at Kishkindha, an important location in Rama’s time. The Bhimanakatte grant aimed at worship at Sītāpura temple also comes with a memory of Ramayana. It appears that the Pandavas during their exile chose to visit the places connected with Rama. They had gone to the cave of Vāli, which is most likely to be Balligavi, earlier known as Vāli-guhe where the Pandavas stayed.

Balligavi must have been the original Kishkindha, visited by Janamejaya. Tirthahalli where Bhimanakatte is situated is approximately 320 kilometer south of Balligavi.

Several places visited by the Pandavas must have been identified by Janamejaya and grants given for the upkeep of those places and the temples therein. All of them were lost in the course of 5000 years. All these grants must have been given after the Sarpa-yāga, the time when he came to know about the history of the Pandavas.

The Bhimanakatte grant endorsing the year of Kali Yuga from which the year of the Mahābhārata war is deduced, offers the first rate primary evidence for the year of the war. The other three grants also are briefly discussed to check the dates.

Three grants of Janamejaya at the Sarpa yāga

Three other grants given by Janamejaya, the son of Parikshit, to the Brahmins of three agrahāras, Begur, Kuppegade and Gauj situated in Shivamogga district have been recorded by Lewis Rice in the 7th and the 8th volumes of Epigraphia Carnatica. Writing about them in the April 1879 issue of The Indian Antiquary, he compared them with another grant, issued by Vira Nolamba, the Cakravarti of Kalyanapura to show the similarities in parts of the Praśasti with the grants of Janamejaya. According to him the Janamejaya grants were forged ones prepared by Brahmins.

Fortunately these grants contain Pancanga features enabling us to check the dates. Vira Nolamba’s grant also contains the complete set of Pancāṅga elements establishing its date as 23rd February 445 CE (Tārana in Śālivāhana Śaka year 366, Phalguni Amāvāsyā, Brihaspati Vāra). The names of the inscriber and the overseeing official also appear in this inscription, but not in the Janamejaya grants.

Two out of three of the Janamejaya inscriptions translated by V.N.Narasimmiyengar in Dec 6, 1872 issue of The Indian Antiquary contain the name “Ramachandra” pleading the future kings and rulers to protect the grants given by Janamejaya! Even this kind of mention of a name is not found in Bhimanakkate grant. No such name in Kedarnath grant too.

The mixture of Sanskrit and Kanarese in the script and the appearance of a part of Praśasti in Vira Nolamba’s inscription make it appear that these three grants were re-written under the authority of Vira Nolamba with Ramachandra as the signatory. Some of the names of boundary locations appearing somewhat modern seem to imply that the boundary lines were re-affirmed under the authority of Vira Nolamba. If these grants were issued by Vira Nolamba, there is no need to write that Janamejaya had made these grants. Retaining the original version of the grants, Vira Nolamba had them re-written by Ramachandra. This is the only plausible deduction.

The three grants of Janamejaya found at Begur, Kuppagade and Gauj contain different time elements showing different dates or time of donation during the Sarpa-yāga, but all of them were handed over to them by Janamejaya in front of Harihara shrine at the confluence of Thunga and Haridra rivers in Shivamogga district. The Bhimanakatte grant also was given at the same location only. It appears that they were personally given by the king Janamejaya on his Dik-Vijaya, though the offerings were made during the course of the Sarpa-yāga.

Based on the Pancanga elements given by Lewis Rice, the dates of these three grants are listed down.

• Begur

Year name and Year number: Not given

Pancāṅga details: Caitra month, Krishna pakśa Tritīya tithi, Tuesday, Indrabha star (Visakha, ruled by the deity Indra. ‘Bha’ means star. Indra’s star).

When checked the years close to Plavanga, the 89th year of Yudhishthira Śaka, it was found that two Caitra months occurred in the previous year, one of them being Adhika māsa. The Pancanga details exactly match together for Adhika Caitra.

The date: January 10, 3014 BCE, Year Parābhava, 88th year of Yudhiṣṭhira Śaka, 28th regnal year of the King Janamejaya.

- Kuppagade

The place is written as Pushpagade in the grant, the original name during Mahabharata times.

Year name and Year number: Not given

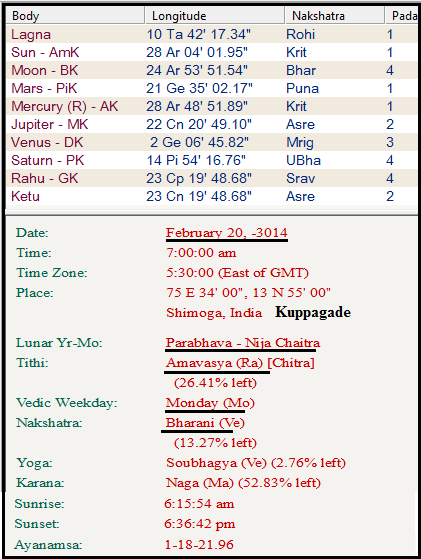

Pancāṅga details: Caitra month, Krishna pakśa, Monday, Bharani star.

When checked for both Adhika and Nija Caitra, it was found to match with Nija Caitra. The tithi was Amāvāsyā.

The date: February 20, 3014 BCE, Year Parābhava, 88th year of Yudhiṣṭhira Śaka, 28th regnal year of the King Janamejaya.

• Gauj

Year name and Year number: Not given

Pancāṅga details: Caitra month, Amāvāsyā, Vyatipāta (yoga), Uttarāyana, Partial solar eclipse (Lewis Rice in The Indian Antiquary, April 1879)

As given in Kuppagade grant and additionally solar eclipse (V.N. Narasimmiyengar in The Indian Antiquary, Dec 6, 1872)

The discrepancy in the details leads us to reject this grant for dating. However the presence of a solar eclipse, not seen in Kuppagade grant (Caitra month) made me suspect transcription error and look for the Uttarayana time.

A solar eclipse did occur at the beginning of Uttarayana in the same year, Parābhava.

The date: November 12, 3014 BCE. Year Parābhava, 88th year of Yudhiṣṭhira Śaka, 28th regnal year of the King Janamejaya.

Rahu was at a distance of less than 10 degrees from the sun, causing the eclipse. Uttarayana started after zero degree Capricorn in this year, while it was at zero degree Capricorn at the time of 3101 BCE when Kali Yuga began)

Discussion:

• The Pancāṅga elements of all the three grants are simulated accurately in the Jhora software. The perfect matching of the time elements show that the inscriptions were genuine and not foreged.

• The dates authenticte the first Śaka as Yudhiṣṭhira Śaka, which by itself is a validation of Kali Maha Yuga that started at 3101 BCE.

• The Śaka year of the Bhimanakatte grant offers first hand confirmation of the ascension of Parikshit to the throne 88 year before that, following the abdication of the Pandavas and the departure of Krishna in 3101 BCE.

• From this date, the year of Mahābhārata is conclusively established at 3136 BCE.

• There is excellent consistency in the dates of the grants giving hints on the time of the Sarpa-yāga.

• The three grants were given for Vyatipāta yoga, noted for donations. They were given before the day of Vyatipāta in Begur and Kuppagade grants and at the time of Vyatipāta in the Gauj grant.

• Since all the grants mention the time as Sarpa- yāga, it is understood that this yajna was done in the 88th year of Yudhiṣṭhira Śaka, in the year Parābhava when Janamejaya was running his 28th regnal year. This year corresponds to 3014 BCE in Gregorian year (with continuous counting that include zero year).

• There is no information in Mahābhārata on the year and the duration of the Sarpa- yāga. But the yajna had gone on for several months during which time Mahābhārata was recited.

• The three grants show the earliest date as Adhika Caitra and the latest as Pushya Amavasya in the year Parābhava, in the 88th year of Yudhiṣṭhira Śaka.

• The next year, i.e. in Plavanga Janamejaya had issued the grants to the maṭha of Bhimanakatte and of Kedarnath.

• From the version of the grants it is known that the king Janamejaya had personally handed over the copper plates during his sojourn to South India.

• All these three grants along with the Bhimanakatte grant were given in front of the shrine of Harihara at the confluence of Thunga and Haridra rivers.

• It appears that the king had given importance to the date of Bhimanakatte and was perhaps present on that date at the banks of Thunga to offer the waters, while he grant for Kedarnath was given by him after this date, when he made a visit to Kedarnath.

• Thus we arrive at the most important date of Bhimanakatte, November 2, 3013 BCE, Plavanga Pushya Amavasya, exactly a year after a grant was given at Gauj on a solar eclipse day.

• The excellent matching of the dates of the two grants (Begur and Kuppagade given in Adhika and Nija Caitra month) with the simulator goes to prove that the “SURYA SIDDHANTA” ayanamsa setting is the only plausible settings for dating the years close to zero degree ayanamsa of Kali Yuga and the dates coming within a century of Kali Yuga.

• No other ayanamsa setting brought out this result — of Caitra having Adhika māsa in Parābhava in the year 3014 BCE. The grants at Begur and Kuppagade in Caitra cannot be simulated in any setting other than that of Surya Siddhanta with its ayanamsa calculated on the basis of 7200 year cycle of to and fro motion of the equinoxes.

• No western astronomy software can simulate these dates.

Having established the year of Mahābhārata war on the basis of epigraphic evidence, its time that all the controversies on the date must die out.

References:

[1] Agnik Bhattacharya, “Inscriptions — A Major Source of Early Indian History” https://www.academia.edu/8089868/Importance_of_Inscriptions

[2] “Inscriptions in the spotlight” The Hindu, June 06, 2019. https://www.thehindu.com/society/history-and-culture/inscriptions-in-the-spotlight/article27552037.ece

[3] “Vedic Link” The Hindu, March 05, 2010 https://www.thehindu.com/arts/the-vedic-link/article16510701.ece1

[4] Dr.R.Nagaswamy, “New Light on Civil Justice in the Pandya Period” http://tamilartsacademy.com/articles/article07.xml

[5] Mahālingaswāmi temple at Tiruvidaimarudūr. A.R.№265 of 1907 https://www.whatisindia.com/inscriptions/south_indian_inscriptions/volume_3/no_138_141_uttama_chola.html №138

[6] Aryabatiya: 5–10

[7] Vedveer Arya, “The Epoch of Śaka Era: A critical study” http://indiafacts.org/epoch-saka-era-critical-study/

[8] Epigraphia Carnatica, Volume VIII, Sorab Taluq, 71

[9] There are controversies about the identity of Kālidāsa. However from the astrological texts, it is asserted that there were two astrologers by name Kālidāsa, one, the author of Jyothirvidabharana who lived in the 1st century BCE and the other, who authored “Uttara Kālāmrita” an astrological text that contains verses from Nirnaya Sindhu, a 17th century text. Additionally the mix of Telugu language in the text traces the origin of this Kālidāsa to South India.

[10] Jyothirvidabharana: Ch 22, verse 21

[11] Srimad Bhagavatam: 12–2–33

[12] Indian Antiquary, Vol 5, p.70 https://archive.org/details/TheIndianAntiquaryVolV/page/n91/mode/1up

[14] Epigraphia Carnatica, Vol. VIII- Inscriptions in the Shimoga District, Part II- Mysore Archaeological Series

by Mysore, Archaeological Department; Rice, B. Lewis, p.349

[15] http://bheemanakattemutt.com/history/

[16] The Indian Antiquary, Dec 6, 1872, p.375

[17] The sun must be within 19 degrees from the nearest node for a solar eclipse.

[18] Pandit Kota Venkatachelam, “The Age of the Mahabharata War” pp.49–51

[19] Vali’s cave appears in the inscription of Vikramadhitya VI. “Ancient Karnataka History of Tuluva, Vol I, p.17–18

[20] Lewis Rice, “The Indian Antiquary” April 1879, “Two new Chalukya Grants” pp.89–98

[21] Odvachari was the writer, Ari-Raya Mastaka, Tala Prahari was the approving official.

[22] V.N. Narasimmiyengar, “Three Maisur Copper Grants”, The Indian Antiquary, Dec 6, 1872, pp. 375–378

[23] Lewis Rice, “The Indian Antiquary” April 1879, “Two new Chalukya Grants” p.91